Sonofabook

www.cbeditions.com

Saturday, 31 May 2025

"Run up the colours": newsletter May 2025

Early books, above … 176 Interruptions, scheduled for July, is a revised and expanded edition of 99 Interruptions (published in 2022 and now almost out of stock). In Ghost Stations: Essays and Branchlines, scheduled for September, Patrick McGuinness – novelist, poet, translator, editor, critic and speaker of several languages – writes about his personal history, the unofficial histories of places in which he has lived, and some of the lesser-known byways of European literature and art. Both books are available for pre-order now from the website.

The encounter with the bear that resulted in three fractured bones in my neck (see previous newsletter) is now history: the bones have healed, the neck brace I wore night and day for two months has been discarded, the bear has gone over the hill. Early in Master and Commander, one of several old films I watched over the past weeks while slumped on the sofa, Captain Aubrey gives this order: ‘Mr Boyle, run up the colours.’ So I did. Below, a slice of unfinished history: a size-A1 poster of the CBe book covers (and 3 pamphlets, 2 issues of a magazine) 2007 to now. The history is ravelled: some of the books are now out of print, some have gone to other publishers, some have been reprinted with different covers. There’s only one print of the poster; I may print a limited run, but how many people have enough spare wall space for a poster?

Shelf space may be easier. Eighty of the books on the poster are available from the website, either individually or – for bargain-hunters – in one of the Season Ticket bundles, 10 books of your own choice for £75 or 6 for £50. Among them are the last two books of Paul Bailey, who may now be among ‘the riotous dead’ but whose life was celebrated at a memorial service last week in the spirit of the titles of his books: Inheritance and Joie de vivre.

Saturday, 3 May 2025

The Silly Season

The non-story so far … A man announces he’s setting up a press that will ‘focus on literary fiction by men’. He says he plans to publish three books next year. To date, he has taken on nothing. His website (which looks as if it’s been thrown together in 5 minutes) announces a submissions window of just one month (the current one) and offers no explanation at all of why the focus on men. Or any info about, you know, the tedious details of actual publishing: distribution, design, funding, etc. This is a hoax, isn’t it?

The non-story starts becoming a story when The Bookseller picks it up, and then the Guardian and The Times (‘Men-only publisher hopes to fix “imbalance” in world of books’), and then a BBC4 radio programme, and then a list of ‘Ten Independent Publishers to Watch in 2025’ (even though there simply ain’t anything to watch: no books till next year), and then the Guardian again with an op-ed story. The man who is starting the press mutters something about male writers of literary fiction getting a bad deal: they are under-represented, or overlooked. One’s heart bleeds. And suddenly everyone starts quoting statistics at each other – numbers of women/men on prize shortlists and bestseller lists, numbers of men/women working in publishing – and journalists ask agents for soundbites.

It’s quite possible that there are more good women writers around than men. It’s also quite possible that that editors at big commercial publishers are under pressure from their owners to deliver the New Sally Somebody (smart, young, female, photogenic, ticks the boxes). That’s how business – ‘the publishing industry’, ha – works. It is not how small independent publishers work. Some of these publishers do offer ‘correctives’ to mainstream bias – by championing POC or working-class writers or work in translation – and over time they can make a difference; but what I’m looking at here (and I’m putting this as kindly as I can) is a solution in search of a problem. Move along now. The only story here is about the crass, knee-jerk, clickbait way in which anything about books is treated by the media, and even that story isn’t news.

Friday, 11 April 2025

The Other Other Jack

‘How old are you, exactly?’

‘Do you talk to other people in line for the bus or do you just eavesdrop for the cute overheard phrase?’

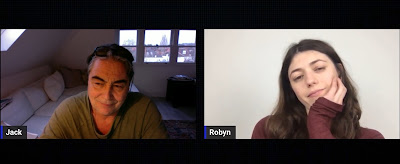

Above is a screenshot from a reading of the stage adaptation of The Other Jack, directed by James Dacre, with Jack (played by Nathaniel Parker) on the left and Robyn (played by Jasmine Blackborow) on the right. The script is by the US playwright and poet Dan O’Brien (CBe has published his poetry and essays). It’s based on the book of the same name by myself, published by CBe in 2021, with some material also coming from 99 Interruptions.

The reading can be streamed free on Vimeo until 22 April – you’ll need to register here with the Lortel Theatre, who will send you a link and a password. It’s an hour and a half long. We are busy people. If you’re pressed for time maybe fast-forward to the five minutes beginning at almost exactly one hour in (1:00).

The original book is loosely constructed around a series of conversations in cafés between a man (a writer, ageing) and a woman (a waitress, much younger). They talk ‘about books, mostly’, according to the cover, but also about ‘bonfires, clichés, dystopias, failure, happiness, jokes, justice, privilege, publishing, rejection, self-loathing, shoplifting and umbrellas’. The man is me, or is me as much as Jack Robinson is me, and here I am being evasive again, something that Robyn picks me up on. The play is not the book and I could say that the Jack in the play is not me but Dan O’Brien’s script is self-effacingly faithful to the book so it is me, whether I like it or not. On the left, smug ageing writer; on the right, young woman concocted to demonstrate writer's self-awareness of his smugness – so that's all right then. There’s something monstrous here.

‘Do you talk to other people in line for the bus or do you just eavesdrop for the cute overheard phrase?’

Above is a screenshot from a reading of the stage adaptation of The Other Jack, directed by James Dacre, with Jack (played by Nathaniel Parker) on the left and Robyn (played by Jasmine Blackborow) on the right. The script is by the US playwright and poet Dan O’Brien (CBe has published his poetry and essays). It’s based on the book of the same name by myself, published by CBe in 2021, with some material also coming from 99 Interruptions.

The reading can be streamed free on Vimeo until 22 April – you’ll need to register here with the Lortel Theatre, who will send you a link and a password. It’s an hour and a half long. We are busy people. If you’re pressed for time maybe fast-forward to the five minutes beginning at almost exactly one hour in (1:00).

The original book is loosely constructed around a series of conversations in cafés between a man (a writer, ageing) and a woman (a waitress, much younger). They talk ‘about books, mostly’, according to the cover, but also about ‘bonfires, clichés, dystopias, failure, happiness, jokes, justice, privilege, publishing, rejection, self-loathing, shoplifting and umbrellas’. The man is me, or is me as much as Jack Robinson is me, and here I am being evasive again, something that Robyn picks me up on. The play is not the book and I could say that the Jack in the play is not me but Dan O’Brien’s script is self-effacingly faithful to the book so it is me, whether I like it or not. On the left, smug ageing writer; on the right, young woman concocted to demonstrate writer's self-awareness of his smugness – so that's all right then. There’s something monstrous here.

Thursday, 3 April 2025

Newsletter April 2025

[Photo of early CBe books by Martina Geccelli]

Invisible Dogs was on the shortlist for the Republic of Consciousness Prize and that was a Good Thing. Congratulations to the winner, Bullaun Press, publisher of Gaëlle Bélem, There’s a Monster Behind the Door, translated from the French by Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert. This prize is designed to reward small presses rather than individual authors or books, and by being on the shortlist CBe nets £1,500, which is more than helpful.

A not-so-good thing is that the distributor has raised charges (i.e, the percentage deducted from sales income on every book sold out of the distributor’s warehouse before it’s passed on to the publisher). And has instituted a new charge on books that sell zero copies over a 3-month period. This charge will affect a large number of CBe titles – currently including books by, among others, Caroline Clark, J. O. Morgan, Beverley Bie Brahic, Roy Watkins, Jack Robinson (me), Dai Vaughan, Nuzhat Bukhari, David Wheatley, Julian Stannard, Dan O’Brien – and potentially, given that in the current 3-month period many other titles are selling only one or two copies, and in the next period may not even do that, many more. Selling small and slow and sometimes zero for 3 months is what many CBe titles do, and I’m fine with that, but I’m being charged here for the privilege of not making money.

Another not-good-thing: two weeks ago I was whacked on the head by a bear that had woken up from hibernation in a grumpy mood. A bone in my neck is fractured and I’ll be wearing a neck brace for some time. This will be a slow year. Two titles published already – 2016, Mrs Calder and the Hyena – and just two to follow. In September, Patrick McGuinness: Ghost Stations: Essays and Branchlines. And 99 Interruptions, published in 2022, is down to just a few copies and needs reprinting, but instead there’ll be a revised and expanded edition: 176 Interruptions.

Bonus extra: a reading of Dan O'Brien's stage adaptation of The Other Jack (with some of 99 Interruptions in there too) is free to sream from the off-Broadway Lucille Lortel Theatre from 8th to 22nd April. Link here. 'There are flirtations, arguments, spilt coffee, deaths both in life and in fiction, generational and gender and cultural conflict, rain and laughter.' Actors: Jasmine Blackborrow, Nathaniel Parker; directed by James Dacre.

I can still walk down to the post office and I need the exercise so please give me a reason. See the website (which includes one or two titles that are officially out of print but a few copies are still available from here; this category may need to increase). And the Season Tickets – 6 books of your own choice for £50, 10 for £75) are still a tariff-free bargain.

Thursday, 27 February 2025

Newsletter February 2025

The shortlist of the 2025 Republic of Consciousness Prize, announced this week, includes Invisible Dogs (CBe). The other books are: There’s A Monster Behind the Door by Gaëlle Bélem, translated by Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert (Bullaun Press); How to Leave the World by Marouane Bakhti, translated by Lara Vergnaud (Divided Press); Célina by Catherine Axelrad, translated by Philip Terry (Les Fugitives); Mother Naked by Glen James Brown (Peninsular Press).

Congratulations to all and many thanks to the judges. Huge thanks to the judges, because they have a job I don’t think I could do. I could go to meet colleagues for brunch in a Turkish restaurant behind Paddington Station – which according to Neil Griffiths, the founder of the prize, writing on the RoC substack, is where they slimmed down the longlist of 10 to the shortlist of 5 – and I could happily choose for myself from the menu but choosing dishes that would please us all would be tricky. Some of us are vegan. Some of us eat meat but not eggs. Some of us (to quote from Neil’s substack) are not even keen on brunch: ‘too in-betweeny’.

The RoC Prize was founded to address a climate in which ‘publishers who could least afford to take the financial risk were left to publish the most risk-taking work’, and its focus has always been on small presses rather than individual books. Every announcement of the long- and shortlists foregrounds the presses over the books and more money goes to them than to the authors or translators. Each press – and the definition of ‘small press’ has required adjustment over the years the prize has been running – is allowed to submit just one book. So is the book being judged as representative of that press, rather than for its individual merit? I don’t think I want to know, just as I really am glad that I didn’t happen to be in that Turkish restaurant and overhear the discussion at the next table. All these prizes, to maintain their fascination, need to retain an air of mystery.

The money is important too. Right now, it looks likely that the money coming to CBe from the RoC long- and shortlistings will enable publication next year of a book I’m keen on and that would otherwise not appear. Two weeks ago I wrote about money on this blog - see the post immediately below this one.

All the RoC shortlisted titles will be celebrated at the Library at Deptford Lounge on 13 March: full details here.

As ever, the Season Tickets on the home page of the CBe website offer a good return: any 6 books from the 79 titles listed for £50, or any 10 books for £75. (There are also specific special offers which change every month or so – 2 books for £16, 3 for £24 – at the foot of the Books page.) Free postage. Beats Amazon. They can be bought for others as well as yourself. No need to wait for Christmas.

Congratulations to all and many thanks to the judges. Huge thanks to the judges, because they have a job I don’t think I could do. I could go to meet colleagues for brunch in a Turkish restaurant behind Paddington Station – which according to Neil Griffiths, the founder of the prize, writing on the RoC substack, is where they slimmed down the longlist of 10 to the shortlist of 5 – and I could happily choose for myself from the menu but choosing dishes that would please us all would be tricky. Some of us are vegan. Some of us eat meat but not eggs. Some of us (to quote from Neil’s substack) are not even keen on brunch: ‘too in-betweeny’.

The RoC Prize was founded to address a climate in which ‘publishers who could least afford to take the financial risk were left to publish the most risk-taking work’, and its focus has always been on small presses rather than individual books. Every announcement of the long- and shortlists foregrounds the presses over the books and more money goes to them than to the authors or translators. Each press – and the definition of ‘small press’ has required adjustment over the years the prize has been running – is allowed to submit just one book. So is the book being judged as representative of that press, rather than for its individual merit? I don’t think I want to know, just as I really am glad that I didn’t happen to be in that Turkish restaurant and overhear the discussion at the next table. All these prizes, to maintain their fascination, need to retain an air of mystery.

The money is important too. Right now, it looks likely that the money coming to CBe from the RoC long- and shortlistings will enable publication next year of a book I’m keen on and that would otherwise not appear. Two weeks ago I wrote about money on this blog - see the post immediately below this one.

All the RoC shortlisted titles will be celebrated at the Library at Deptford Lounge on 13 March: full details here.

As ever, the Season Tickets on the home page of the CBe website offer a good return: any 6 books from the 79 titles listed for £50, or any 10 books for £75. (There are also specific special offers which change every month or so – 2 books for £16, 3 for £24 – at the foot of the Books page.) Free postage. Beats Amazon. They can be bought for others as well as yourself. No need to wait for Christmas.

Sunday, 9 February 2025

Writing and money (and death and sex)

‘Literature is news that stays news,’ said Pound, but the activities of writing, reading and publishing are really not news at all: they are what goes on in the background, usually very quietly, and only get on to the news pages when they involve one or more of the staple ingredients of fiction, whether ‘literary’ fiction or genre: death, sex and money.

This post is about money. In December 2022 the Society of Authors reported on an ALCS (Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society) report under the headline ‘report on author incomes shows 60% drop in median incomes since 2006’. Here is a screenshot of the summary:

The full ALCS report is available from their website as an 86-page pdf download. It records ‘a sustained downward trend [in writers’ income] over the past two decades’. The report acknowledges the ‘lack of a stable definition of “an author”’ – a phrase I like – but was based on responses to survey questions from 60,000 writers. 51% male, 91% white, on the whole middle-aged (age group 55-64 comprising 25% of the total sample); 47% ‘primary occupation author’, 24% ‘all working time spent on writing’, and about half ‘work at least part-time in other employment’.

The Guardian also reported on the ALCS report. Its piece was a press release with quotes from salaried people in other organisations (Society of Authors, Writers’ Guild, Publishers Association) pasted in. No quotes from writers and no digging down. More recently the Guardian reported on another money issue, Baillie Gifford’s withdrawal of sponsorship funding from all literary festivals (the Hay and Edinburgh festivals had already cut free) after protests against BG’s investment in fossil fuel companies; there was much protest against the protestors; there was no mention (that I saw) of the fact that for 99% of writers the disappearance of all literary festivals would make no difference to their income.

(The Guardian’s news pages also cover literary prizes – invariably mentioning in the opening paragraph how much money the winner has bagged – and record auction prices for works of art; deaths of famous authors and artists; and scandals involving plagiarism, forgery and sexual abuse. Death, sex and money. Mostly money.)

Money shouts and literature whispers, so the conversation is always going to be difficult, but especially so in a country that has not just a capitalist economy, society, culture, but mindset. There are Premier League footballers earning £500,000 a week; there are closures and redundancies in the Humanities departments and Creative Writing courses at universities; in the private sector, there are people paying thousands for week-long writing courses on Greek islands with good food and wine. Meanwhile, the Arts Council is scatter-gun but necessary: as well as propping up the big guns (the Royal Opera House, the National Theatre, etc.), it gives cash to people without traditional privilege. It’s a Band-Aid plastered over deep political failure. The countries in Europe – two hours by Eurostar or Ryanair – that offer tax breaks to independent bookshops and restrictions on discounting by online retailers, or where the government buys copies of all new books and distributes them to libraries, seem very far away.

My tribe: writers, artists, gallerists, small-press publishers, booksellers. Not exclusively, far from it; some of the people I love have no interest in books at all. But if any of them is making more than the ALCS 2022 median income of £7,000 from their writing, painting, showing, publishing, they are rare exceptions. My point here is not to counter arguments that we are not ‘professional’ because we don’t make money (we are professional); and not to suggest that we don’t need paying because we are ‘incentivised’ by ‘love of creating’ (we also like a roof over our heads, and food); and not to claim that we are especially resilient or somehow ‘heroic’ (no). This is simply how it is, though you wouldn’t know it from how writing is reported in the news. And not from the ads for writing courses that promise to ‘take your writing to a new level’ or ‘progress your career’, with advice from ‘industry experts’.

Like most writers, like many small presses, CB editions makes a loss, every year; a sustainable loss, to date; a healthy loss, because it keeps me on my toes. CBe has never had Arts Council funding for any of its books but of course it is subsidised – by my state pension, by my bus pass, by my having picked up design and typesetting know-how in previous work so I don’t have to pay for these, by my freelance work for others, by my living in a country in which there are people who have ‘disposable income’. This isn’t news.

This post is about money. In December 2022 the Society of Authors reported on an ALCS (Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society) report under the headline ‘report on author incomes shows 60% drop in median incomes since 2006’. Here is a screenshot of the summary:

The full ALCS report is available from their website as an 86-page pdf download. It records ‘a sustained downward trend [in writers’ income] over the past two decades’. The report acknowledges the ‘lack of a stable definition of “an author”’ – a phrase I like – but was based on responses to survey questions from 60,000 writers. 51% male, 91% white, on the whole middle-aged (age group 55-64 comprising 25% of the total sample); 47% ‘primary occupation author’, 24% ‘all working time spent on writing’, and about half ‘work at least part-time in other employment’.

The Guardian also reported on the ALCS report. Its piece was a press release with quotes from salaried people in other organisations (Society of Authors, Writers’ Guild, Publishers Association) pasted in. No quotes from writers and no digging down. More recently the Guardian reported on another money issue, Baillie Gifford’s withdrawal of sponsorship funding from all literary festivals (the Hay and Edinburgh festivals had already cut free) after protests against BG’s investment in fossil fuel companies; there was much protest against the protestors; there was no mention (that I saw) of the fact that for 99% of writers the disappearance of all literary festivals would make no difference to their income.

(The Guardian’s news pages also cover literary prizes – invariably mentioning in the opening paragraph how much money the winner has bagged – and record auction prices for works of art; deaths of famous authors and artists; and scandals involving plagiarism, forgery and sexual abuse. Death, sex and money. Mostly money.)

Money shouts and literature whispers, so the conversation is always going to be difficult, but especially so in a country that has not just a capitalist economy, society, culture, but mindset. There are Premier League footballers earning £500,000 a week; there are closures and redundancies in the Humanities departments and Creative Writing courses at universities; in the private sector, there are people paying thousands for week-long writing courses on Greek islands with good food and wine. Meanwhile, the Arts Council is scatter-gun but necessary: as well as propping up the big guns (the Royal Opera House, the National Theatre, etc.), it gives cash to people without traditional privilege. It’s a Band-Aid plastered over deep political failure. The countries in Europe – two hours by Eurostar or Ryanair – that offer tax breaks to independent bookshops and restrictions on discounting by online retailers, or where the government buys copies of all new books and distributes them to libraries, seem very far away.

My tribe: writers, artists, gallerists, small-press publishers, booksellers. Not exclusively, far from it; some of the people I love have no interest in books at all. But if any of them is making more than the ALCS 2022 median income of £7,000 from their writing, painting, showing, publishing, they are rare exceptions. My point here is not to counter arguments that we are not ‘professional’ because we don’t make money (we are professional); and not to suggest that we don’t need paying because we are ‘incentivised’ by ‘love of creating’ (we also like a roof over our heads, and food); and not to claim that we are especially resilient or somehow ‘heroic’ (no). This is simply how it is, though you wouldn’t know it from how writing is reported in the news. And not from the ads for writing courses that promise to ‘take your writing to a new level’ or ‘progress your career’, with advice from ‘industry experts’.

Like most writers, like many small presses, CB editions makes a loss, every year; a sustainable loss, to date; a healthy loss, because it keeps me on my toes. CBe has never had Arts Council funding for any of its books but of course it is subsidised – by my state pension, by my bus pass, by my having picked up design and typesetting know-how in previous work so I don’t have to pay for these, by my freelance work for others, by my living in a country in which there are people who have ‘disposable income’. This isn’t news.

Friday, 17 January 2025

2025: 2016 and the Hyena

First newsletter of the year. The news is – happily, and thanks mainly to some very loyal readers – that there is no news, in the sense that some very good books are being written and CBe will be publishing a very small number of them during 2025.

Finished copies of the first two 2025 books are in and can be ordered from the website. First, Mrs Calder and the Hyena, short stories by Marjorie Ann Watts, which will be officially published on 28 January, the author’s 98th birthday. [Ed.: Surely some mistake? No – no typo there, no mistake.]

Second, 2016 by Sarah Hesketh. 2016 was quite a year: David Bowie died in January and Leicester City won the Premier League in May and Jo Cox was murdered in June and in November many good people still thought that Donald Trump could not possibly be elected President of the US … Fergal Keane: 2016 ‘vividly, stirringly defies categorisation. It is a story, a poem, an oral history, a series of arguments about an epoch, and who and what we are becoming.’

Later in the year, Patrick McGuinness’s Ghost Stations: Essays and Branchlines. And a novel, maybe. And maybe more interruptions (99 Interruptions is down to a few last copies but they don’t stop at 99).

On the 13 February you have a tricky choice: Sarah Hesketh will be reading from 2016 at Shakespeare and Company in Paris, and on the same evening Will Eaves will be reading from Invasion of the Polyhedrons and Beverley Bie Brahic from her Carcanet collection Apple Thieves at the Broadway Bookshop in London: more details here. Beverley Bie Brahic’s Hunting the Boar and her translations of Apollinaire (The Little Auto) and Francis Ponge (Unfinished Ode to Mud) are still in print with CBe; as are several previous titles by Will Eaves, including The Absent Therapist and Broken Consort.

As always, the new titles can be included in the Season Tickets: 6 books of your own choice for £50, or 10 for £75, free UK postage. Available from the home page of the website. I like going to the post office: below, post receipts from the past months, kept for tax purposes and to stuff my shoes when the leather wears out.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)