Tuesday 6 December 2022

Artefictions

Surprise package: files of The Camden Town Hoard, published by Studio Expurgamento with CB editions, were sent to the printer today. Finished books before Christmas, if the stars align. The book can be ordered now from the website.

From the introduction by Natalia Zagórska-Thomas: ‘The Camden Town Hoard is a collection of archaeological finds dredged up from a section of Regent’s Canal, roughly between Granary Square in Kings Cross and the London Zoo. The canal was dredged by an unknown person in the spring/summer of 2021 during lockdown. The majority of the objects revealed during this time were removed from the canal towpaths by Camden Council but not before 20 or so most fascinating artefacts were rescued and accessioned into the ExPurgamento archive. Since then the collection has been studied, thoroughly documented and provided with museum labels by a team of highly trained experts from a broad variety of backgrounds and interests … Identifying and contextualising the various objects threw up several new problems related to taxonomical classification. Specifically, it has been noted that the term “artefact” may not be an entirely sufficient or appropriate description of all archaeological material and it is therefore proposed that the term “artefiction” might sometimes be used instead.’

Six books for £40, anyone? Or 12 for £75? See the Season Tickets on the website home page. For yourself or as a gift to someone else (and I’ll do the posting).

Last Sunday, at the launch of the archive catalogue of Nick Wadley – artist and art historian, 1935–2017 – at Tate Britain, we had the rare and moving privilege of being able to leaf through his sketchbooks (below). Three books of Nick Wadley’s drawings were published by Dalkey Archive. A pamphlet of 14 of his drawings (‘on bookish and related matters’) was published by CBe in 2012 – copies are available free to the next 10 people who sign up for one of the Season Tickets.

Monday 14 November 2022

0 to around 80 in 15 years

Fifteen years ago this month I collected the first books from the printer, 10 minutes from where I live. I was happy and deeply disappointed: now that I had the bound copies in my hand I could see that the inside margins were around 3mm too narrow. The readers wouldn’t notice, most of them, but I did. An uncle had died and left me £2,000 and the previous August I’d had the notion of spending this money on publishing four books: my uncle’s money paid for 250 copies of each. There weren’t going to be any more. But then there were. Below, the first four books, and a photo taken this summer of every title published to date.

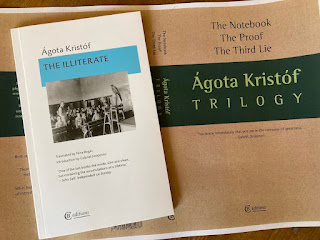

The following month, in an attempt to make the books more visible, I started this blog (this was 2007). On the very first day – 21 December – I wrote four short posts, and going back to them is strange. The first post is titled ‘Blush’, which happens to be title and subject of a collaborative book CBe eventually got around to publishing in 2019. The second post has the photo, used above, of the first four books. The fourth post has a photo of a schoolroom in Hungary in the 1930s which hung around for a while, waiting to features on the cover of Ágota Kristóf’s The Illiterate, published this year.

A snapshot history of CBe, written in instalments over the years, is downloadable (pdf) from the ‘About and News’ page of the website.

Also available from the website home page, not one but two Season Tickets. The original is still there, 12 books for £75, free delivery, but 12 books amount to a big ask so there’s now a 6-books-for-£40 option as well. If you are wondering what to give X or Y for Christmas, here is your answer. Thank you, everyone who stopped by and picked up a book.

The following month, in an attempt to make the books more visible, I started this blog (this was 2007). On the very first day – 21 December – I wrote four short posts, and going back to them is strange. The first post is titled ‘Blush’, which happens to be title and subject of a collaborative book CBe eventually got around to publishing in 2019. The second post has the photo, used above, of the first four books. The fourth post has a photo of a schoolroom in Hungary in the 1930s which hung around for a while, waiting to features on the cover of Ágota Kristóf’s The Illiterate, published this year.

A snapshot history of CBe, written in instalments over the years, is downloadable (pdf) from the ‘About and News’ page of the website.

Also available from the website home page, not one but two Season Tickets. The original is still there, 12 books for £75, free delivery, but 12 books amount to a big ask so there’s now a 6-books-for-£40 option as well. If you are wondering what to give X or Y for Christmas, here is your answer. Thank you, everyone who stopped by and picked up a book.

Monday 12 September 2022

'Everybody has gone mad"

‘They crowned a king this day, and there has been great rejoicing and elaborate tomfoolery, and I am perplexed and saddened.’ That’s Jack London writing about the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 in The People of the Abyss, a book I quote from extensively in the final chapter of Good Morning, Mr Crusoe. ‘The Socialists, Democrats, and Republicans went off to the country for a breath of fresh air, quite unaffected by the fact that 40 millions of people were taking to themselves a crowned and anointed ruler. Six thousand five hundred prelates, priests, statesmen, princes, and warriors beheld the crowning and anointing … throughout the crowd were flung long lines of the Metropolitan Constabulary, while in the rear were the reserves – tall, well-fed men, with weapons to wield and muscles to wield them, in case of need.’

‘And now the Horse Guards, a glimpse of beautiful cream ponies, and a golden panoply, a hurricane of cheers, the crashing of hands – “The King! the King! God save the King!” Everybody has gone mad. The contagion is sweeping me off my feet. I, too, want to shout, “The King! God save the King!” Ragged men about me, tears in their eyes, are tossing up their hats and crying ecstatically, Bless ’em! Bless ’em!” See, there he is, in that wondrous golden coach, the great crown flashing on his head, and a woman in white beside him … And I check myself with a rush, striving to convince myself that it is all real and rational, and not some glimpse of fairyland. This I cannot succeed in doing …’

Jack London was living in the East End and writing as a journalist, with researched statistics: in this brief chapter on the 1902 coronation – an episode in the continuation of an institution that still, according to the marketing department, unites the nation – he notes that ‘five hundred hereditary peers own one-fifth of England’ and spend ‘32 per cent of the total wealth produced by all the toilers of the country’; and that in London, ‘one in four adults is destined to die on public charity, either in the workhouse, the infirmary, or the asylum’.

Read The People of the Abyss (preferably in the 2014 edition published by Tangerine Press, which reproduces the photographs included in the original 1903 edition). Of course I’d also like to sell copies of Good Morning, Mr Crusoe, which is about imperial mythology (racism and misogyny included in the package) and how historically much of Eng Lit has been co-opted by that. And, officially published this month, Caroline Clark’s Own Sweet Time and my own 99 Interruptions. And please be aware that the Season Ticket – available from the home page of the website: 12 books for £75 – is still going: started at the beginning of the first Covid lockdown in March 2020, so by now an institution, almost, less history than the monarchy but I hope more future. Actually, now would do.

Saturday 30 July 2022

On photographs of books

Way back when, maybe 20 years ago, I wandered by chance into an exhibition of photographs by Martina Geccelli at the Goethe Institut in London: photographs not of the covers of books and not the spines but the opposite of the spines – the loose page edges, gathered but hanging free. In 2010 I got in touch with Martina and in an act of extraordinary generosity she took photos of the early CBe books and said I could use them for free. The above photograph is from a sequence of 14 (deserving fine-art reproduction, better than this blogpost). Another is on the cover of by the same author.

Martina Geccelli photographs books like Morandi painted jugs. She now runs RAUMX, a project space within her own studio in north London: ‘an open, intimate platform, outside of the commercial setting of a gallery’. Her website (not up to date but still good) has more books and examples of her other photographs (including plastic bags, pallets, and abandoned offices in the World Trade Center in NY, where she had a residency in 2000).

99% of photographs of books are photos of product, commissioned by marketing departments. They show flat fronts and elicit comments on the cover design (though frankly, until you’ve seen the spines and the backs this feels premature). Other than Geccelli, one of the very few photographers I know of who is interested in the physical form of books is the Cuban-born Abelardo Morrell. A link to some of his book photos is here, and below is ‘Dictionary', 1994:

Admittedly, Morrell favours books that are old. Books need wear and tear, or dust and neglect, to take on character. Here’s my own copy of Middlemarch, which I took on holiday and left outside on a damp night:

*

Photos of books being read are a different thing. Among the most famous are the (posed) photos by Eve Arnold of Marilyn Monroe reading Ulysses. What’s going on here? Even if the official message was She’s not just a ditzy blonde, there was no way through: men of a certain ilk like their ditzy blondes to read posh, it’s cute. Adding a link here to the list of books owned/read by Marilyn Monroe, who was far from dumb, won’t change that.

The best photos of books being read are the 65 (unposed) photos in On Reading by André Kertész. Here’s a photo of a CBe book being not read, and (posed) the aftermath:

*

A photo I took last week of 15 years of CBe (82 books, 3 pamphlets, 2 issues of a magazine, 1 CD) owes a debt – in concept, not in execution – to Martina Geccelli:

Here's the official version. And then the whole rickety edifice came tumbling down:

Saturday 23 July 2022

Serve chilled

Finished copies of all these beauts, pretty little things, CBeebies – I need a series title for them: suggestions welcome – are now in: Agota Kristof, The Illiterate; Charles Boyle, 99 Interruptions; Caroline Clark, Own Sweet Time. They are small (A-format: 178 x 112mm) and slim (the longest is 82 pages).

£8.99 for one of those? Yes, actually. Like the temperatures last week, printing costs are hitting record highs. But if you scroll to the bottom of the Books page on the website you can get all three for £24; and if you press the Season Ticket button on the Home page you can choose them for £6.25 each. (The Season Ticket has been tweaked: up by £5 in price but more books for your cash, up from 10 to 12 books of your own choosing.)

They have insides as well as fronts and backs. I wrote about the Kristof’s The Illiterate here. 99 Interruptions is in some ways a sequel to The Other Jack, published last year (but life rarely proceeds in a straight line). Caroline Clark’s Own Sweet Time offers two texts, running parallel on the versos and rectos; for more about ‘one of the most tender and moving books due to be released this year’, listen to this Rippling Pages podcast.

There are many precedents. New Directions offer Bolano, Bulgakov, Gogol, etc, in a slim A-format minimalist-designed series titled Pearls. Melville House offer novellas by Chekhov, Maupassant, Kate Chopin, etc, in a wide A-format. OUP offer more than 700 books in their excellent A-format Very Short Introductions series (one of best publishing projects in recent decades; titles range from Abolitionism to Zionism and include Terry Eagleton on ‘The Meaning of Life’). Among the most desirable A-formats – both for their content and because they are now scarce – are the Cape Editions published in the late 1960s and edited by Nathaniel Tarn; below is a handful from my shelves:

No one is reinventing the wheel here. But these are good wheels. Buy while stocks last. Read within one month of opening. Serve chilled.

Sunday 10 July 2022

How many books in a caravan?

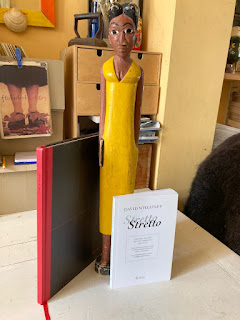

Roy Watkins’ Simple Annals is on the shortlist of three for the PEN Ackerley Prize, which is wonderful news. David Wheatley’s Stretto, published in June, is reviewed in the current issue of the Literary Review: Adorno and Walter Benjamin are invoked but happily the text is ‘leavened … with moments of properly Beckettian bathos.’

I’ve been on holiday (a proper one, with beaches and sunburn and platefuls of fish) and I need more space. Poor sales through the distributor during Covid lockdowns have helped to trigger a formula – relating sales of a given title over the past 3 years to the amount of copies in stock – according to which the distributor is (rightly) entitled to charge storage. Stock reduction at the distributor’s warehouse means the arrival of a van at my front door with boxes and boxes (I’ve lost count) of books. One way to solve the resulting space problem would be to build an aircraft hangar in my back garden. Or I could buy a caravan and ask a friend to let me park it in his driveway. Or – I’m trying to be realistic here – I could sell more books through the website. I commend to you, again, the Season Ticket button on the website home page: 10 books of your own choice over 10 weeks for £70, free postage. (That’s a saving of at least 25% on each title, I think; if you include Agota Kristof’s Trilogy, you’re saving 50% on the cover price of that book alone.

Two September titles – Caroline Clark, Own Sweet Time and me, 99 Interruptions – are up on the website for pre-order. They are short and small and £8.99 each may seem a bit steep but let me tell you (another time) about hikes in printing costs. If you include them in your Season Ticket choices, of course, you get them for £7 each. These books and Kristof’s The Illiterate are a new, white-cover look; I’ll write more about this later.

If there are any CBe readers who would like to come to a summer party in west London next Sunday, the 17th, email me.

Saturday 4 June 2022

The 1922 Committee and Cicely Hamilton

The 1922 committee is the parliamentary committee to which Tory MPs send letters if they want to ditch Johnson. (Emails? I think not: letters written with quills on parchment more likely, but I’m not a Tory MP so I don’t know the etiquette.) The best-known members of the literary 1922 committee are T.S. Eliot and James Joyce, who in that year both published modernist masterpieces that changed … Changed what, exactly? This post celebrates the centenary of a little-known but remarkable novel by Cicely Hamilton, and also her book on men–women relations. The texts are from my 2019 book on Robinson Crusoe (hence the references to Defoe and Crusoe).

Theodore Savage (1922) by Cicely Hamilton – who worked in military hospitals in France throughout the 1914–18 war and saw what happens when bombs are dropped from the air and poison gas is released […] Theodore Savage is a civil servant who works ‘without urgence, for limited hours, in a room that looked on Whitehall’, and is knowledgeable about music and art (‘his treasured Fragonard and his bell-toned Georgian wine-glasses’). He falls in love with his boss’s daughter and, ‘red to the ears and stammering platitudes’, he asks her father’s permission to marry her in, where else, the library, while daring to hope that this father will not ‘insist upon too lengthy an engagement’. His timing is not good. The world’s dominant political organisation, a kind of gentlemen’s club of the wealthiest nations, miscalculates its response to a challenge to its authority, and war breaks out. This is war as enabled by the new technology: ‘displacement of population, not victory in the field, became the real military objective’. Driven from the cities by aerial bombardment, starving millions roam the countryside, where crops and livestock are destroyed by chemical weapons. Within weeks, the structure of society – ‘laws, systems, habits of body and mind’ – has crumbled, ‘leaving nothing but animal fear and the animal need to be fed’. ‘Man, with bewildering rapidity, was slipping through the stages whereby, through the striving of long generations, he had raised himself from primitive barbarism.’

With survival now depending on brute force, women fare badly, and ‘those women suffered most who had no man of their own to forage and fend for them, and were no longer young enough for other men to look on with pleasure’. One of these women, Ada, a former factory worker, attaches herself to Savage. The pair become a mocking echo of Crusoe and Friday (and Hamilton’s exposition of their relationship is far more acute than the saccharine version of master-and-servant in Defoe’s novel). Savage treats Ada ‘as a backward child’, ‘an encumbrance’; only after he returns one day from a foraging expedition with some women’s clothes, which she delights in, does he become aware of her as a sexual being. But they cannot enjoy each other as equals: Ada is ‘flaccid, lazy, infantile of mind’ and Savage cannot get beyond his awareness that Ada is ‘so plainly his mental inferior’. Savage beats her (‘she wriggled, plunged and howled’); she accepts the beating; she expects the beating. Only by physically acting out the power imbalance between them can they live together, forging a bond that accords with ‘the barbaric institution of marriage’ and its traditions ‘of wifely obedience’.

Savage and Ada, now pregnant, are absorbed into a ragged tribe of survivors bound together ‘not by the love its members bore to each other, but by hatred and fear of the outsider’. Before he is accepted, Savage is questioned about his background. Because in this post-apocalypse world all links to the science and engineering that have enabled the Ruin are being cut – knowledge is being undone, a revenge upon ‘progress’ – Theodore Savage, educated at a public school and then Oxford, proficient in Latin and possessing impeccable good taste, is permitted to live only because in the pre-Ruin society he spent all his working life in admin, writing letters and reports and filing them, and has no specialist skills and is essentially useless.

---------

Writing about sex often involves writing about status, power and money. Defoe was interested in all of these, and in the links between them. Walter de la Mare, noting Defoe’s worldliness, remarks that he ‘was fully as much interested in wives as in tradesmen’ – an odd pairing, on the face of it, but a telling one. Defoe was himself a tradesman – at various times he sold wine, hosiery, woollen goods and tobacco; he owned a factory that made bricks and tiles; he bred civet cats for perfume; he invested in a diving bell to recover treasure from wrecked Spanish galleons; and he wrote extensively on the subject. Writing, for Defoe, was a trade. Trade was how a man made his way in the world and, in this early capitalist society and for more than two centuries after, a woman too – although for the latter the almost exclusive means of advancement was founded upon surrender.

In Marriage as a Trade – published in 1909, in the same decade that Thomas Godolphin Rooper was bleating about ‘the dominion of the Anglo-Saxon’ and a Cambridge University Press edition of Robinson Crusoe was celebrating Britain as ‘the greatest colonizing power in the world’ – Cicely Hamilton argues that for women denied access to both education and employment, marriage is the compulsory deal made for economic survival. She was writing mostly about middle-class women (‘a class persistently set apart for the duties of sexual attraction, house-ordering and the bearing of children’), not factory workers like Ada in her novel Theodore Savage and not ‘the prostitute class – a class which has pushed to its logical conclusion the principle that woman exists by virtue of a wage paid her in return for the possession of her person’. Hamilton was of her time (as I am of mine) in some of her assumptions: that women are more ‘fastidious’ in sex than men; that child-raising and fulfilment in work are incompatible. But she nailed it, the basic contract of marriage: ‘essentially (from the woman’s point of view) a commercial or trade undertaking’. Denied fulfilment of her own interests, it was demanded of a woman only ‘that she should enkindle and satisfy the desire of the male, who would thereupon admit her to such share of the property he possessed or earned as should seem good to him. In other words, she exchanged, by the ordinary process of barter, possession of her person for the means of existence.’

Chapter by chapter, Hamilton explores the consequences of women being raised solely to become ‘unintelligent breeding-machines’ who are ‘fed and lodged on the same principle a horse is fed and lodged – so that she may do her work, her cooking, her cleaning, her sewing, and the tending and rearing of her children’. None of those activities is more ‘naturally’ women’s work than men’s: ‘woman, as we know her today,’ Hamilton argues, ‘is largely a manufactured product; the particular qualities which are supposed to be inherent in her and characteristic of her sex are often enough nothing more than the characteristics of a repressed class and the entirely artificial result of her surroundings and training.’ The whole pattern is bizarre and illogical: women are trained for ‘sex and motherhood’ but about sex itself and the risk of STDs ‘there exists a conspiracy of silence’; and the constrictions imposed upon women ‘have defeated their own ends by discouraging the intelligence which ought to be a necessary qualification for motherhood, even if it is not a necessary qualification for wifehood’. But power trumps logic, power owns logic: given ‘the deep-rooted masculine conviction that [woman] exists not for her own benefit and advantage, but for the comfort and convenience of man’, then ‘The masculine attitude in this matter seems quite logical.’

‘One wonders,’ writes Hamilton calmly but also with anger, ‘what it has meant for the race – this persistent need of the man to despise his wife, this economic need of countless women to arrest their mental growth?’ Nine years after Marriage as a Trade was published the right to vote in parliamentary elections in the UK was granted to women (aged over 30, and there were other limitations), but Hamilton’s question has still not been addressed.

Tuesday 31 May 2022

To reprint or not to reprint?

Recently I told an author I had no copies left of one of her books and had no plans to reprint. I felt a little guilty. She shrugged and smiled, as if to say ‘It was fun, and now it’s over.’ Was she just being kind?

Ars longa, vita brevis – but really most art is pretty brevis too. Some of the books published by CBe are no longer available because I’ve let them go out of print: Erik Houston, The White Room; Jack Robinson, Days and Nights in W12; Elise Valmorbida, The TV President; Jack Robinson, Recessional; Gabriel Josipovici, Only Joking; Nancy Gaffield, Tokaido Road; Beverley Bie Brahic, White Sheets; Fergus Allen, New and Selected Poems. Most will have an afterlife of sorts on Abebooks. (There are also a few titles which you’ll be told are out of print if you try to order them from a bookshop, but I still have a few copies left at home so they are available from the website.)

Some other titles originally published by CBe are no longer on the list because they were taken over by other, bigger publishers: Jennie Walker, 24 for 3; Christopher Reid, The Song of Lunch; May-Lan Tan, Things to Make and Break; Will Eaves, Murmur. And some dropped off because the publishing license I’d paid for was for only a limited period of time or a limited print run: David Markson, This Is Not a Novel; Agota Kristof, The Notebook and 2 Novels, also The Illiterate. But I’ve stumped up again for the Kristofs, which are now back. I need to sell some copies.

When stock is down to just a handful of copies, how do I decide whether to reprint or not? It’s not a scientific process, how could it be. (Nor is deciding on the size of an initial print run: I close my eyes and think of a number. Nor is deciding which books to publish in the first place.) It’s partly about whether I have any expectation of selling more than one or two copies in the next year, and partly about money (in short print runs, each book costs more to print), and partly about whether I think a particular title is a core part of the list. Francis Ponge, Unfinished Ode to Mud, trans. BB Brahic, first published in 2008, will be staying in print. Last year I reprinted Andrzej Bursa, Killing Auntie and other work, trans. Wiesiek Powaga.

Copies of a reprint of Dan O’Brien’s War Reporter (Fenton Aldeburgh Prize, 2013; Forward-prize shortlisted) are now in. I’ve put the cover price up from £8.99 to £10.99. On the other hand, if you order War Reporter from the website in the next week or so I’ll add in O’Brien’s New Life (in which he continues his engagement with the reporter Paul Watson) for free. ‘Out of the War Zone: A Conversation between Paul Watson and Dan O’Brien’ was published on the LARB website two days ago.

Ars longa, vita brevis – but really most art is pretty brevis too. Some of the books published by CBe are no longer available because I’ve let them go out of print: Erik Houston, The White Room; Jack Robinson, Days and Nights in W12; Elise Valmorbida, The TV President; Jack Robinson, Recessional; Gabriel Josipovici, Only Joking; Nancy Gaffield, Tokaido Road; Beverley Bie Brahic, White Sheets; Fergus Allen, New and Selected Poems. Most will have an afterlife of sorts on Abebooks. (There are also a few titles which you’ll be told are out of print if you try to order them from a bookshop, but I still have a few copies left at home so they are available from the website.)

Some other titles originally published by CBe are no longer on the list because they were taken over by other, bigger publishers: Jennie Walker, 24 for 3; Christopher Reid, The Song of Lunch; May-Lan Tan, Things to Make and Break; Will Eaves, Murmur. And some dropped off because the publishing license I’d paid for was for only a limited period of time or a limited print run: David Markson, This Is Not a Novel; Agota Kristof, The Notebook and 2 Novels, also The Illiterate. But I’ve stumped up again for the Kristofs, which are now back. I need to sell some copies.

When stock is down to just a handful of copies, how do I decide whether to reprint or not? It’s not a scientific process, how could it be. (Nor is deciding on the size of an initial print run: I close my eyes and think of a number. Nor is deciding which books to publish in the first place.) It’s partly about whether I have any expectation of selling more than one or two copies in the next year, and partly about money (in short print runs, each book costs more to print), and partly about whether I think a particular title is a core part of the list. Francis Ponge, Unfinished Ode to Mud, trans. BB Brahic, first published in 2008, will be staying in print. Last year I reprinted Andrzej Bursa, Killing Auntie and other work, trans. Wiesiek Powaga.

Copies of a reprint of Dan O’Brien’s War Reporter (Fenton Aldeburgh Prize, 2013; Forward-prize shortlisted) are now in. I’ve put the cover price up from £8.99 to £10.99. On the other hand, if you order War Reporter from the website in the next week or so I’ll add in O’Brien’s New Life (in which he continues his engagement with the reporter Paul Watson) for free. ‘Out of the War Zone: A Conversation between Paul Watson and Dan O’Brien’ was published on the LARB website two days ago.

Tuesday 10 May 2022

Post-Tweet

I took this photo yesterday morning – rubbish collection day in Acton: it spoke to me – and posted it on Twitter, saying I’m useless at selling books. I mentioned reviews of a particular title (but not naming it, and including no link). Then I went out. I came home to orders for 30 books from the website and three more Season Ticket subscriptions. And an offer of some free publicity in the Falkland Islands.

I get some things right, some things wrong. Sometimes what I think I’m doing right turns out to be wrong, and vice versa, and this is normal. Selling, like most things, is not an exact science. Science is not an exact science. Many of the books I publish (and read) are not obvious ‘bestsellers’, but that doesn’t excuse me from trying to get the books to as many readers as I can, and I should be doing better. The wonder is, CBe is still puttering along after 15 years. Meanwhile, thank you very much indeed to everyone who has bought even a single book.

The Season Ticket deal, by the way: 10 books of your own choice for £70, post free (UK only). Available from the website home page. It knocks all similar offers from other publishers into a cocked hat.

Monday 25 April 2022

The Ledger (and Stretto)

I’m going to make a lectern and give readings. It’s sort of a holy book.

When the first four CBe books came out in November 2007 I had no plans to publish more, so I kept track of sales and expenses on scraps of paper, but between September 2008 and March 2022 all the basic accounting has been done by hand in this ledger. It records (in handwriting; I don’t do spreadsheets) more than 3,700 individual orders from the website. Plus direct sales to bookshops, at book fairs, etc. And against those, printing costs, advances, royalties, couriers, prize entry fees, stationery, website costs, proofreading, publicity (hah), review copies, etc. And post: receipts recorded from 1,883 trips to the post office (which, thankfully, is very close, but that still adds up to a few miles). It doesn’t record typesetting or design costs because there are no costs, I just do it.

Also recorded are 150 trips to the distributor, Central Books, with boxes of books. These used to be by car but I gave up the car a while ago so now they are by Tube and then train to Essex with a very big bag. I can do that, go and return, and have tea with Bill if he’s in, and be home by lunchtime.

To do the end-of-tax-year figures I add in figures from other sources: income from sales through the distributor to bookshops (less their own cut and that of the sales agent + VAT, which I’m not registered for so can’t reclaim), PayPal fees, etc. But the basic day-to-day running numbers are all here, in the ledger, handwritten. And it’s full, so at the beginning of April this year I started a new one.

The old ledger and I have shared a desk for 14 years. I’m a scrivener, basically, and writing figures in columns gives me the illusion that I’m in control. I still don’t quite trust digital, and the internet.

There’s something nerdy here, obviously. Some people do crosswords, daily. I once worked with a Faber poet who claimed he read every word in his page proofs backwards. The narrator of Stretto writes about his ytiliba ot klat, sey, sdrawkcab – his ability to talk, yes, backwards. He puts it down ‘to my being left-handed, and not predisposed to treat left-to-right as the natural order of things other people take it to be’. I’m left-handed too. There are more of us than you think and we are all a little sceptical about ‘the natural order of things’. Stretto, a first novel by a writer already known as a poet and critic, is a novel that interests itself in this.

If you’d like your name in the new ledger – below, with an advance proof of Stretto – please buy a book. Finished copies of David Wheatley’s Stretto will be here in a couple of weeks, and it’s available for pre-order; copies of Ágota Kristóf’s Trilogy and The Illiterate are now in. Or buy, even, a Season Ticket – available from the website home page – which nets you 10 books of your own choice for £70, post free.

Sunday 3 April 2022

Ágota Kristóf: the books, not the blurbs

The blurb on the back of the 2014 CBe edition of Kristóf’s The Notebook declared that Kristof distils the experience of occupation and ‘liberation’ in Europe during World War II into a ‘stark fable of timeless relevance’. Did I really mean that, or was it just a fancy piece of blurbspeak?

Leaders in ‘the West’, no less than Putin,* have for decades been speaking in blurbspeak: ‘defending democracy’, ‘standing up against dictators’, the UK’s ‘generosity’ to refugees, other ritual phrases (‘of timeless relevance’) that tick boxes but whose idiotic repetition has so drained them of meaning they’ve become as divorced from reality as mission statements on white vans delivering dogfood. Deliberately so, after reducing the practice of democracy to selling stuff and getting/staying rich.

When the children in Kristóf’s The Notebook are left with their grandmother by their mother, they mockingly repeat ‘the old words’ their mother used to say to them: ‘“My darlings! My loves! I love you … I shall never leave you …’” – ‘By repeating them we make these words gradually lose their meaning.’ In their own writing they reject words like nice and beautiful and love – ‘because the word “love” is not a definite word, it lacks precision and objectivity’. They have one rule: ‘the composition must be true. We must describe what is, what we see, what we hear, what we do.’

Another sentence from the early pages of The Notebook: ‘We smell of a mixture of manure, fish, grass, mushrooms, smoke, milk, cheese, mud, clay, earth, sweat, urine and mould.’ And from the first page of Kristóf’s brief memoir, The Illiterate, about her childhood and refugee-hood:

‘My father’s classroom smells of chalk, ink, paper, calm, silence and snow, even in summer. My mother’s kitchen smells of slaughtered animals, boiled meat, milk, jam, bread, wet laundry, baby’s pee, agitation, noise, and summer heat, even in winter.’

That’s a blurb, right there. And rather than blurbing that Kristóf’s books are ‘about the after-effects of trauma and the nature of storytelling’ – which I have done, those words are on the covers, I’m trying to sell stuff too within a system in which the unsubscribe-to-blurbspeak button is blocked – it might be more honest to simply ask: What do the classroom and the kitchen smell of after they’ve been hit by bombs?**

In 2014 CBe published The IIliterate (translated into English for the first time by Nina Bogin) alongside The Notebook, and in 2015 the two sequels to The Notebook, The Proof and The Third Lie. Under license (I didn’t, and don’t, have money to pay for more): UK rights for 5 years only and limited print runs, so in around 2019 these books fell off the list. Damn. They are now back, officially published in June but I’ve sent them to print and they’re on the website for pre-order: the three novels in a single volume, Trilogy (the biggest book CBe has published: 338 pages),*** and The Illiterate (skinny: 54 pages) in a white-cover A-format edition (there’ll be more of these).

Kristóf fled Hungary in 1956, aged 21, smuggled over the border with her 4-month-old baby and her husband during the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising. No time to say goodbye to her parents and brothers. Two bags: kid-stuff and dictionaries. Writing in a language she began to learn during cigarette breaks in the factory in Switzerland where she worked as a refugee, for Kristóf blurbspeak was never an option because she didn’t have that vocab. From The Illiterate: ‘I have spoken French for more than thirty years, I have written in French for twenty years, but I still don’t know it. I don’t speak it without mistakes, and I can only write it with the help of dictionaries.’ What words mean is important. I simply cannot imagine Kristóf using a phrase such as ‘defending democracy’.

Kristóf was a reader and then a writer and her books are shocking but her status as a refugee was and is not special. There are thousands of Kristófs living around the corner from me in London, each of them wondering every day ‘What would my life have been like if I hadn’t left my country?’ and many of them answering as Kristóf does: ‘More difficult, poorer, I think, but also less solitary, less torn. Happy, maybe.’

--------------------------

* The present UK government is Putin-lite: get rich, suppress protest and information, despise women and foreigners, drown refugees, rewrite history to suit your agenda. Carried out under cover of the convenient elision of capitalism and democracy. They didn’t know he’d actually bomb hospitals? Rather than just underfund them and then sell them off cheap to oligarchs (we have plenty of our own)? He’s gone a little too far? The Tory party and Putin are different in degree but not kind.

** That is not a rhetorical question. I live in an off-shore island that for several hundred years has had no experience of being invaded and occupied but instead has actively invaded and occupied other countries and by what right do we lecture Putin? Again, not a rhetorical question. It can be answered, it needs to be answered, but not in blurbspeak.

*** At £14 Kristóf’s Trilogy is not just the longest but the priciest CBe book to date. Gas and electricity, also printing costs (rising for the past several months) and (rising again this week) postage costs … But if you choose it as one of your 10 books-for-£70 Season Ticket – see the website home page – you’ll be getting it at a more than Amazonian half price. I make deals, with myself and others.

Tuesday 1 March 2022

Putinesque in the Cotswolds

Paul Bailey’s Joie de vivre was celebrated at Daunts in Holland Park on Wednesday last week. It was joyful, there was joie de vivre, and I could post photos to illustrate that but not now. This is not the right week.

Among the poems Paul read was one from the Kurdish, starting: ‘When the first people were fleeing, I fled. / When the first fires were started, I was burnt.’ The Kurdish man he had the original from, not a poet at all, was there.

Another poem for the book, about the body of a migrant child washed up on a beach, didn’t make the cut. How to write that poem better? How to live better? ‘“There’s no one to say,” she said flatly.’ That’s the reply given by a woman in a novel I’m currently reading to a man who has just said, in the course of a desultory domestic argument, ‘I wish someone would tell me how I can live.’

There I go again, back into books. I’m bookish. Books are important but they are not that important. Instead of a photo of a book launch, here’s a picture of a Putinesque building designed ‘for an estate in the Cotswolds near the village of Chipping Norton, UK’. If the owners run out of milk, they can pop next door to David Cameron. I’m sure his fridge is well stocked. ‘Named St John's House, the 6,692-square-metre home has been drafted for a 60-acre site that is currently being sold by Sotheby’s International Realty.’ After 24 February there may be fewer shell companies owned by Russian oligarchs in the bidding queue but there are still plenty others this government of shopkeepers kowtows to. What's happening in Ukraine is happening not least because of the continued greed, corruption and complicity with Putin this country has consistently voted into power.

Among the poems Paul read was one from the Kurdish, starting: ‘When the first people were fleeing, I fled. / When the first fires were started, I was burnt.’ The Kurdish man he had the original from, not a poet at all, was there.

Another poem for the book, about the body of a migrant child washed up on a beach, didn’t make the cut. How to write that poem better? How to live better? ‘“There’s no one to say,” she said flatly.’ That’s the reply given by a woman in a novel I’m currently reading to a man who has just said, in the course of a desultory domestic argument, ‘I wish someone would tell me how I can live.’

There I go again, back into books. I’m bookish. Books are important but they are not that important. Instead of a photo of a book launch, here’s a picture of a Putinesque building designed ‘for an estate in the Cotswolds near the village of Chipping Norton, UK’. If the owners run out of milk, they can pop next door to David Cameron. I’m sure his fridge is well stocked. ‘Named St John's House, the 6,692-square-metre home has been drafted for a 60-acre site that is currently being sold by Sotheby’s International Realty.’ After 24 February there may be fewer shell companies owned by Russian oligarchs in the bidding queue but there are still plenty others this government of shopkeepers kowtows to. What's happening in Ukraine is happening not least because of the continued greed, corruption and complicity with Putin this country has consistently voted into power.

Sunday 13 February 2022

2007–2022

I’m getting the ducks in a row for 2022. Paul Bailey’s Joie de vivre is already here and will be officially (by which I mean joyously) launched at Daunts, Holland Park, on 23 February. June: Stretto, a novel by David Wheatley, well-known as a poet but there are things you can do in prose you can’t do in poetry and here are some of them. Later in the year, say September, essays by the multi-tasking Patrick McGuinness (poet, novelist, translator, academic, critic; Tunisia, Belgium, Wales).

Also: a reissue of Agota Kristof’s trilogy (The Notebook, The Proof, The Third Lie), previously published by CBe in two volumes in 2014 and 2015, and her brief memoir, The Illiterate. And slim A-format books from Caroline Clark (after Sovetica last year) and me (after The Other Jack last year). Given the recent steep rise in printing costs, slim-and-small makes senses.

2022 is the fifteenth anniversary of the start date of CB editions, 2007. The photo above was taken outside the CBe pop-up shop in Portobello Road back in 2013. CBe has no Arts Council funding and relies entirely on sales to stay afloat. Huge thanks to those readers who have taken up the 10-books-for-£70 offer and welcome to new readers – see ‘Season Ticket’ on the website home page, from where a complete list of CBe publications, 2007–2022, can be downloaded.

Friday 28 January 2022

CBe in 2022

As I come out of hibernation, CBe in 2022 is beginning to take shape.

First, a second poetry collection by Paul Bailey, who began publishing his distinguished fiction in 1967, has been Booker-Prize shortlisted twice, and has a new lease of life in poetry. Ali Smith on his first collection, Inheritance, from CBe in 2019: ‘Unsentimental, funny, affectionate, deeply moving, the poems read almost off-the-cuff but work at levels of exactness, kindness and observation that throw open a whole closed century of English class-shift and time-shift … A slim, calm volume whose resonance is huge.’ Joie de vivre, the new book, is here.

To follow … Stretto, a radical and audacious debut novel, as the blurbspeak has it, by the poet David Wheatley. It ‘takes its title from a musical term describing the effect when a fugue subject begins to duplicate and accompany itself before it has finished, causing a complex pile-up’. Later, essays by the polymath (poet, novelist, memoirist, critic, editor, translator) Patrick McGuinness. And maybe Andrew Elliott will resurface. And maybe the start of a new series of short A-format books (which I’d like to call ‘smalls’ but won’t).

And not least, a reissue of Agota Kristof’s trilogy: The Notebook, The Proof, The Third Lie. The English translations were first published in 1986 and the early 1990s; CBe reissued them in 2014 and 2015; CBe’s license to publish lapsed but is now back in place. Possibly accompanied by a reissue of Kristof’s brief memoir The Illiterate, if only I can persuade the rights-holders that CBe can sell a serious number of copies.

Kristof was born Csikvánd, a village in Hungary, in 1935. ‘My father is the only schoolteacher in the village. He teaches all the grades, from the first to the sixth, in the same classroom …’ The above photo is how I imagine that classroom; for no apparent narrative reason, a falcon makes a brief appearance in The Proof. In 1956, aged 21, Kristof fled the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising with her husband and infant daughter and became a refugee in Switzerland. She wrote in French, a language ‘imposed on me by fate, by chance, by circumstance’, a language that ‘is killing my mother tongue’; her books are acts of resistance and their renewed presence on the CBe list is, to me, important.

For an interview with Kristof, see here. There’s a half-hour documentary on Kristof made in Switzerland in 2011 which I’d like to see but the app through which I need to pay to watch is unavailable in the UK. Any helpful suggestions will be welcome.

Parish notes: a gentle reminder that the Season Ticket available on the home page of the website – 10 books over 10 weeks for £70, post-free in the UK – has made all the difference over the Covid period. (Just 19 books were sold through the distributor this month. Neither paper costs nor heating costs are going down.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)