Sunday, 3 April 2022

Ágota Kristóf: the books, not the blurbs

The blurb on the back of the 2014 CBe edition of Kristóf’s The Notebook declared that Kristof distils the experience of occupation and ‘liberation’ in Europe during World War II into a ‘stark fable of timeless relevance’. Did I really mean that, or was it just a fancy piece of blurbspeak?

Leaders in ‘the West’, no less than Putin,* have for decades been speaking in blurbspeak: ‘defending democracy’, ‘standing up against dictators’, the UK’s ‘generosity’ to refugees, other ritual phrases (‘of timeless relevance’) that tick boxes but whose idiotic repetition has so drained them of meaning they’ve become as divorced from reality as mission statements on white vans delivering dogfood. Deliberately so, after reducing the practice of democracy to selling stuff and getting/staying rich.

When the children in Kristóf’s The Notebook are left with their grandmother by their mother, they mockingly repeat ‘the old words’ their mother used to say to them: ‘“My darlings! My loves! I love you … I shall never leave you …’” – ‘By repeating them we make these words gradually lose their meaning.’ In their own writing they reject words like nice and beautiful and love – ‘because the word “love” is not a definite word, it lacks precision and objectivity’. They have one rule: ‘the composition must be true. We must describe what is, what we see, what we hear, what we do.’

Another sentence from the early pages of The Notebook: ‘We smell of a mixture of manure, fish, grass, mushrooms, smoke, milk, cheese, mud, clay, earth, sweat, urine and mould.’ And from the first page of Kristóf’s brief memoir, The Illiterate, about her childhood and refugee-hood:

‘My father’s classroom smells of chalk, ink, paper, calm, silence and snow, even in summer. My mother’s kitchen smells of slaughtered animals, boiled meat, milk, jam, bread, wet laundry, baby’s pee, agitation, noise, and summer heat, even in winter.’

That’s a blurb, right there. And rather than blurbing that Kristóf’s books are ‘about the after-effects of trauma and the nature of storytelling’ – which I have done, those words are on the covers, I’m trying to sell stuff too within a system in which the unsubscribe-to-blurbspeak button is blocked – it might be more honest to simply ask: What do the classroom and the kitchen smell of after they’ve been hit by bombs?**

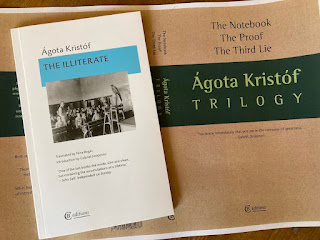

In 2014 CBe published The IIliterate (translated into English for the first time by Nina Bogin) alongside The Notebook, and in 2015 the two sequels to The Notebook, The Proof and The Third Lie. Under license (I didn’t, and don’t, have money to pay for more): UK rights for 5 years only and limited print runs, so in around 2019 these books fell off the list. Damn. They are now back, officially published in June but I’ve sent them to print and they’re on the website for pre-order: the three novels in a single volume, Trilogy (the biggest book CBe has published: 338 pages),*** and The Illiterate (skinny: 54 pages) in a white-cover A-format edition (there’ll be more of these).

Kristóf fled Hungary in 1956, aged 21, smuggled over the border with her 4-month-old baby and her husband during the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Uprising. No time to say goodbye to her parents and brothers. Two bags: kid-stuff and dictionaries. Writing in a language she began to learn during cigarette breaks in the factory in Switzerland where she worked as a refugee, for Kristóf blurbspeak was never an option because she didn’t have that vocab. From The Illiterate: ‘I have spoken French for more than thirty years, I have written in French for twenty years, but I still don’t know it. I don’t speak it without mistakes, and I can only write it with the help of dictionaries.’ What words mean is important. I simply cannot imagine Kristóf using a phrase such as ‘defending democracy’.

Kristóf was a reader and then a writer and her books are shocking but her status as a refugee was and is not special. There are thousands of Kristófs living around the corner from me in London, each of them wondering every day ‘What would my life have been like if I hadn’t left my country?’ and many of them answering as Kristóf does: ‘More difficult, poorer, I think, but also less solitary, less torn. Happy, maybe.’

--------------------------

* The present UK government is Putin-lite: get rich, suppress protest and information, despise women and foreigners, drown refugees, rewrite history to suit your agenda. Carried out under cover of the convenient elision of capitalism and democracy. They didn’t know he’d actually bomb hospitals? Rather than just underfund them and then sell them off cheap to oligarchs (we have plenty of our own)? He’s gone a little too far? The Tory party and Putin are different in degree but not kind.

** That is not a rhetorical question. I live in an off-shore island that for several hundred years has had no experience of being invaded and occupied but instead has actively invaded and occupied other countries and by what right do we lecture Putin? Again, not a rhetorical question. It can be answered, it needs to be answered, but not in blurbspeak.

*** At £14 Kristóf’s Trilogy is not just the longest but the priciest CBe book to date. Gas and electricity, also printing costs (rising for the past several months) and (rising again this week) postage costs … But if you choose it as one of your 10 books-for-£70 Season Ticket – see the website home page – you’ll be getting it at a more than Amazonian half price. I make deals, with myself and others.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment